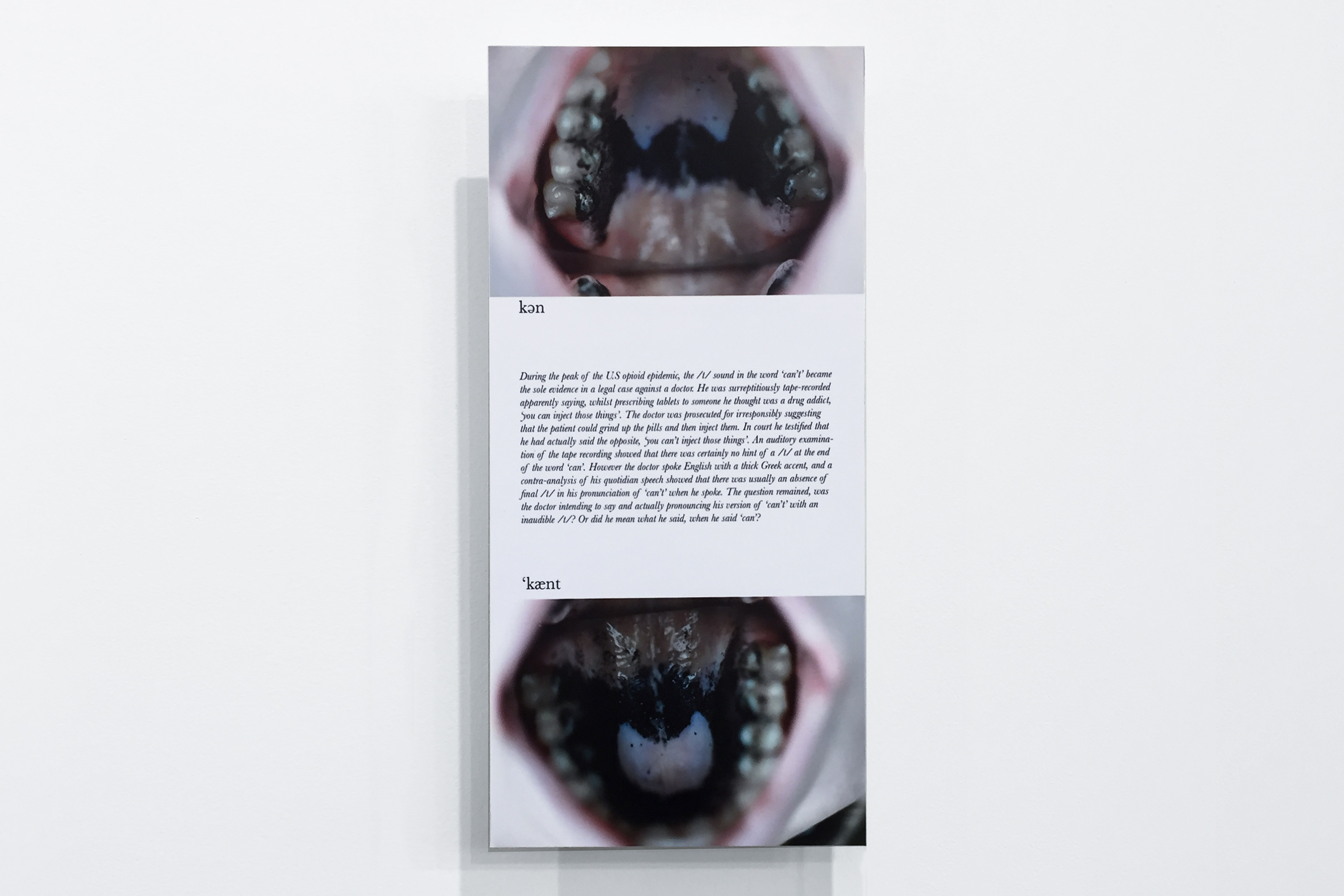

As yet untitled 7, 2018

glass, glue, metal brackets, paper

46 × 60 × 20 1/2 in; 116.8 × 152.4 × 52.1 cm

image Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. photo: FLORIAN KLEINEFENN

–

The German word Icht means any thing, or any such thing. The word has nearly vanished in modern language, having survived only in Nichts—nothing, (or no-thing), which was formed out of the two words in (meaning no) and icht (any such thing) as in-icht. If we subtract the T from Icht, the Ich remains—the German equivalent to the I. Embedded and included in Icht, in any such thing, is the I, the inherent I of any such thing.

The subtracted T is also the mathematical nomen for transcendental numbers, numbers that have been first suspected to exist by the mathematicians Leibniz or Euler, who wrote that there must be numbers that exceed algebraic calculation, numbers that are impossible to grasp. Known transcendental numbers, proven to exist in the middle of the 19th century, are at the same time rare—the most famous being Pi—and supposedly many, but yet unknown, and mathematicians seemingly wait for them to spring up somewhere. As a rule they are irrational.

“The mathematical proof of the transcendence of numbers allowed the proof of the impossibility of several ancient geometric constructions involving straightedge, and including the most famous one, squaring the circle.” (Wikipedia)

Transcendental numbers are also performative numbers, that extend while we calculate them. They resemble double mirrored images, waving at us from infinity, a glassy contingency, transparent, because approachable–you can always start on their path, but you will not see the end–, yet caught in themselves and in their own rules. On their way they never connect, but like the number Pi they sometimes play with connections, or emulate them. They sometimes seem to hide in known series of numbers, faking known results of calculations but then wander off on their own unruly path towards infinity.

The known transcendental numbers stem from spatial operations like squaring the circle, or calculating the space under a curve, calculations which recall social operations. When they are used—again in mathematical terms—within the “ratio of integers,” they are used in their imprecise approximations, by negating their performativity. How familiar «ratio of integers» sounds. A ratio of a whole, into which performativity cannot be squeezed.

HENRIK OLESEN’s exhibition at Gallery Chantal Crousel is not a linguistic operation at which this text may seem to hint, but what lies in the practise of opposing concepts, of mirroring them into their embedded infinity. It is about things opposed to bodies, as is sculpture at its core, adding an irrational that very simply distorts space. I also see them in the concepts of the Ichts, these Is in their bodily presence sent into the incalculability of time, where their existence performes as a screen for projections, identifications and feelings, being reminded of what Walter Benjamin writes about the I, and especially the I in the novels of Proust and Kafka: He writes: “When Proust in his Recherche du temps perdu, and Kafka, in his diaries, use I, for both of them it is equally transparent, glassy. Its chambers have no local coloring; every reader can occupy it today and move out tomorrow. You can survey them and get to know them without having to be in the least attached to them. In these authors the subject adopts the protective colouring of the planet, which will turn grey in the coming catastrophes.”

While HENRIK OLESEN knows, that the protective coloring of the planet is vulnerable, and especially today again, he is proposing communities, love, and friendship, as irrational agents, as incalculable Ts, and as traces on the outside, as well as traces of the making of the self, within its self-mirrored image. — ARIANE MÜLLER, press release for the exhibition HENRIK OLESEN, 6 or 7 new works presented at Chantal Crousel, Paris.

The exhibition 6 or 7 new works from which the work presented above was part of, was on view from April 28th to May 27th, 2018 at Chantal Crousel Paris.