Remco Torenbosch. Integration

Porter (2017)

installation view at Saloon, Brussels, April-Mai 2017

–

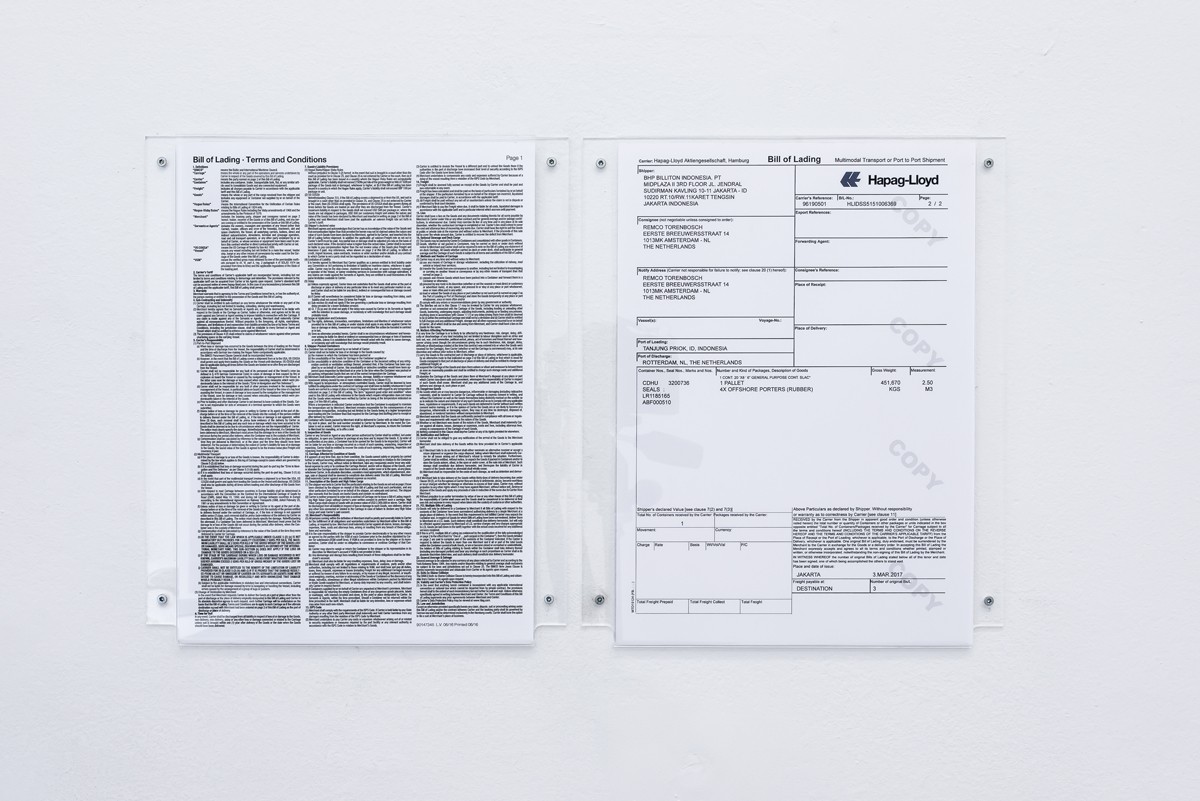

Porter (2017)

installation view at Saloon, Brussels, April-Mai 2017

–

Porter (2017)

installation view at Saloon, Brussels, April-Mai 2017

–

Integration, installation view at Saloon, Brussel, April-May 2017

–

Integration, installation view at Saloon, Brussel, April-May 2017

–

Miner (2014-2017)

installation view at Saloon, Brussels, April-Mai 2017

–

Integration, installation view at Saloon, Brussel, April-May 2017

–

Integration, installation view at Saloon, Brussel, April-May 2017

all images: courtesy the artist and Saloon, Brussels

photography: LOLA PERTSOWSKY

–

REMCO TORENBOSCH‘s practice is essentially research-based and explores concrete economic, politic and cultural situations that he is using in a way to ideologically question their context.

In his Saloon exhibition, Integration, TORENBOSCH deals with two companies rooted in the former Dutch colonies: tin mining company Billiton Maatschappij and natural rubber production company Rubber Cultuur Maatschappij Amsterdam. These two multinationals were established during the last period of the colonial Indonesian occupation by the Dutch, which formed the Dutch East Indies (1816—1949) .

TORENBOSCH was interested by these two industries for their significant role played in the dematerialization of the contemporary digitalized economy.

After analysing the production and distributional data of both companies in the national archives, and visiting several tin mines and rubber plantations on Sumatra and Java in 2015, TORENBOSCH presents a series of ready-made objects as sculptures including Porter (2017) and Miner (2014-2017):

Miner (2014—2017) focuses on the Miner, a crypto mining computer that virtually collects crypto currency, yet requires physical mining of ‘conflict minerals’ to produce its hardware. Torenbosch’s interest in crypto currency was triggered by the heavy contradiction and overlap found in the jargon that surrounds it such as ‘mining’, ‘mining pools’, and ‘workers’. This terminology of physical labour used in fully automated labour counteracts the agonizing physical mining that is needed to produce the printed circuit boards of the actual miner. In the early 1970s, 20 years after the Indonesian National Revolution that officially acknowledged Indonesia’s independence, oil and gas company Royal Dutch Shell acquired the former colonial company Billiton Maatschappij. This acquisition accelerated the mining growth, turning Indonesia into one of the world’s largest producers of tin. From that point on tin became a commodity mainly used for hardware for electronic devices like computers. During his research for this exhibition Torenbosch came across the miners that are on display in Integration. These miners are manufactured in Jakarta, Indonesia, the former capital of the Dutch East Indies and the former epicentre of trading networks in Asia. The circuit boards of these miners contain tin that was physically mined at the Bangka-Belitung islands in South Sumatra Indonesia. Here, the Billiton Maatschappij started its mining, hence the islands became the namesake of the company. In 2001, a fusion of Billiton Maatschappij and the Australian BHP formed BHP Billiton, which later became the largest mining company in the world.

Porter (2017) is a collection of rubber objects used for offshore and deep sea mining. The works are connected to the Dutch East Indies Rubber Cultuur Maatschappij Amsterdam, a leading exporter of natural rubber during the late colonial period. In 1856 it started to produce and collect its high quality natural rubber at several plantations on Sumatra and Java. The company played an influential role as one of the most prominent suppliers of insulation rubber used for the wiring of the British All Red Line that started in 1858. The line was a transatlantic telegraph cable to connect the colonies to the west and ran through the Dutch territory of Java. It is historically seen as the forerunner of the submarine fiber optic cables which are a main instrument of international virtual trade in which transactions are made digital. Originally, the objects in the exhibition functioned as insulation material of water and sound during the process of automated offshore and deep sea mining. They are made of synthetic rubber that since the industrial revolution overruled the industry of natural rubber due to its low production costs. In these objects, traces of usage of offshore mining and natural marks by salt water are noticeable but abstract. Like the miner computers, these objects distribute the shifting notion between physical labour and automation that centralize the paradox of how a dematerialized and digital world emerged from a materialized one with physical labour at its core.*

Integration by REMCO TORENBOSCH is on view at Saloon, Brussels until May 7, 2017.

–

*press release from Saloon, Brussels

–

comments are closed !